Fighting Fire with Fire: Do Rate Hikes Stop Greed-flation?

By Mathew Harris

Blair Fix recently wrote 3 posts on interest rates and inflation totaling over 60 pages. He has some great nuggets in there, but he wasn’t the best at expressing them which I think lead to him being run through the Twitter wringer. I’m going to summarize it because I think the data analysis is worth taking seriously, and near the end I’ll also mention some hurdles that I see.

Skip Ahead:

A summary of Blair’s work.

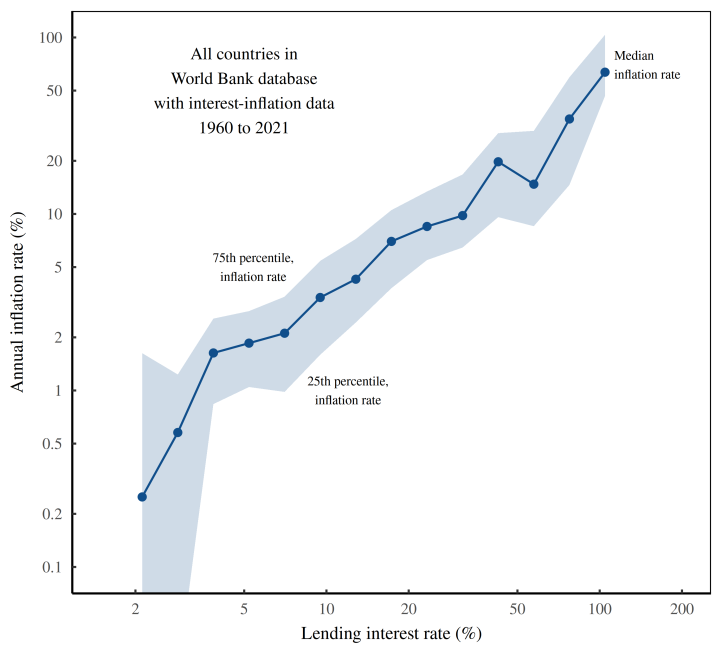

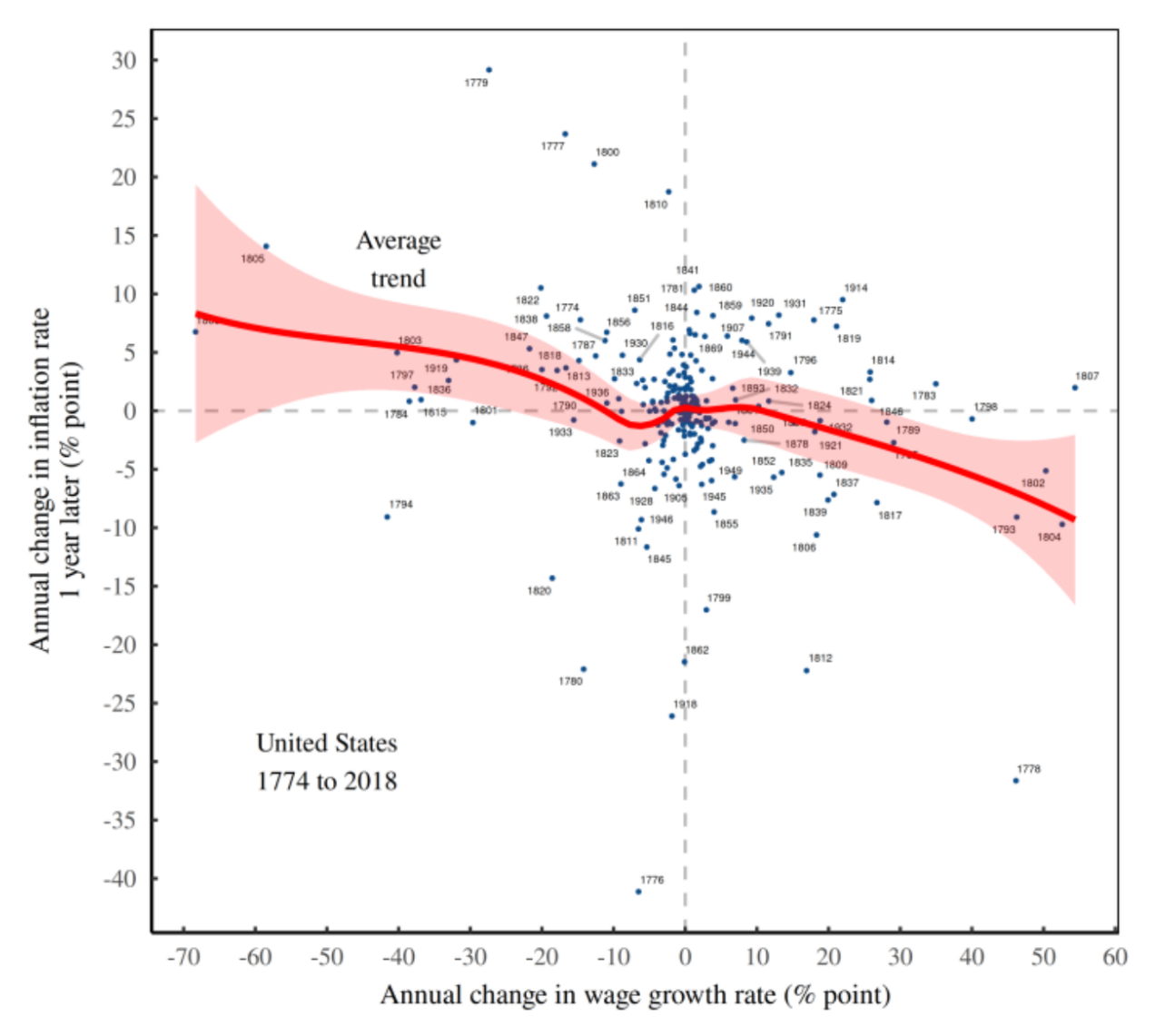

To start us off we’re going to look at the Fisher Effect. This is the correlation between inflation and interest rates and below is Blair’s graphs

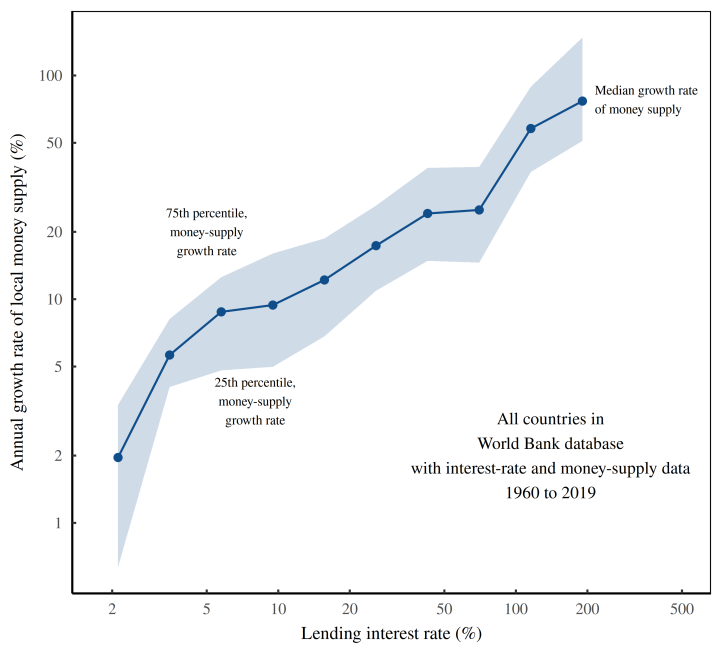

Interest rates also happen to correlate with the money supply as shown here.

For a lot of people, these two graphs should be no surprise. Interest rates are used to control the money supply as a response to inflation. It then stands to reason that it will correlate with the two.

It’s been over 100 years however and we have more data and more tools than when Fisher theorized this in 1907. Let’s talk about lags. Typically, when economists talk about inflation, whether it’s the cause or the cure, the lags are “long and varied”. To be blunt, this is just an excuse to wait forever until the circumstances change to fit your prediction/prophecy. Since highschool I’ve heard folks scream that QE will “eventually” cause inflation (or hyperinflation) yet we had 3% for over a decade.

Thats how lags shouldn’t be used, how should they be used? Lags can be used to infer precedence which then gives us hints at what is less dominant. Lags are also used to show autocorrelation, though frequently in regression analysis it’s assumed there is none and this is skipped (which occasionally results in errors).

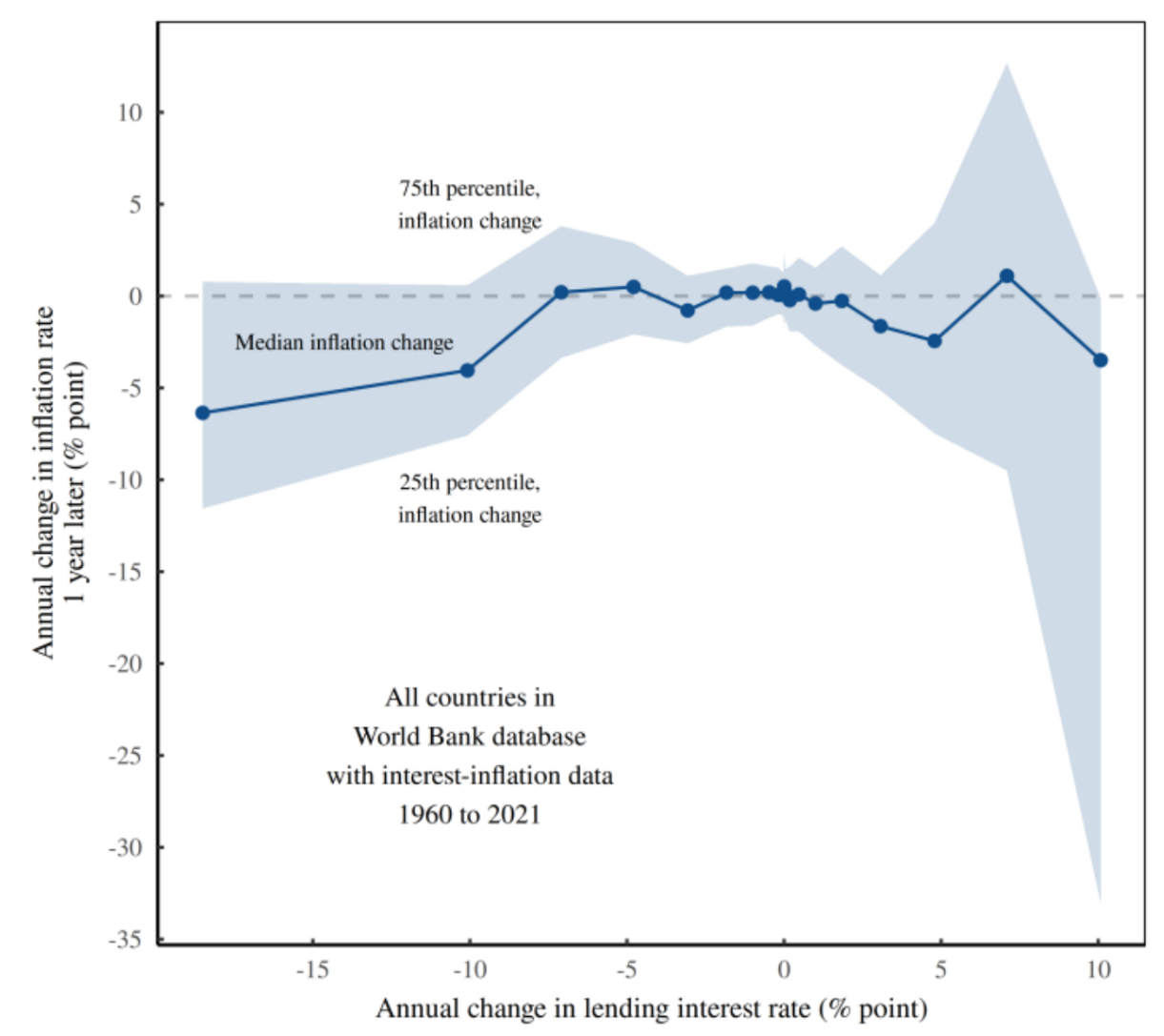

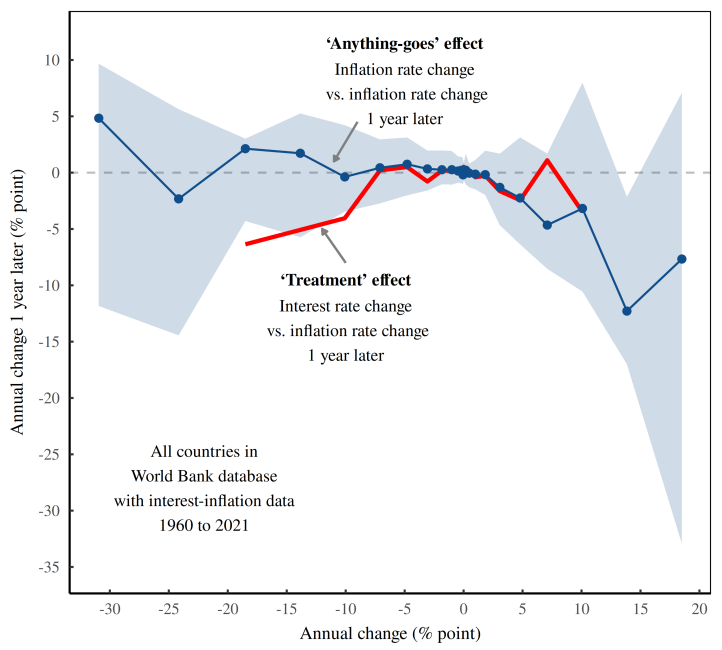

With that in mind, we will compare annual interest-rate changes to annual inflation changes in the following year across counties.

The trend is pretty muddy, but it looks like large interest-rate drops are associated with decreases in next-year’s inflation. This is the opposite of what we expect. It also happens to be what Turkey did in 2022 and everyone thought it was crazy. More on that later.

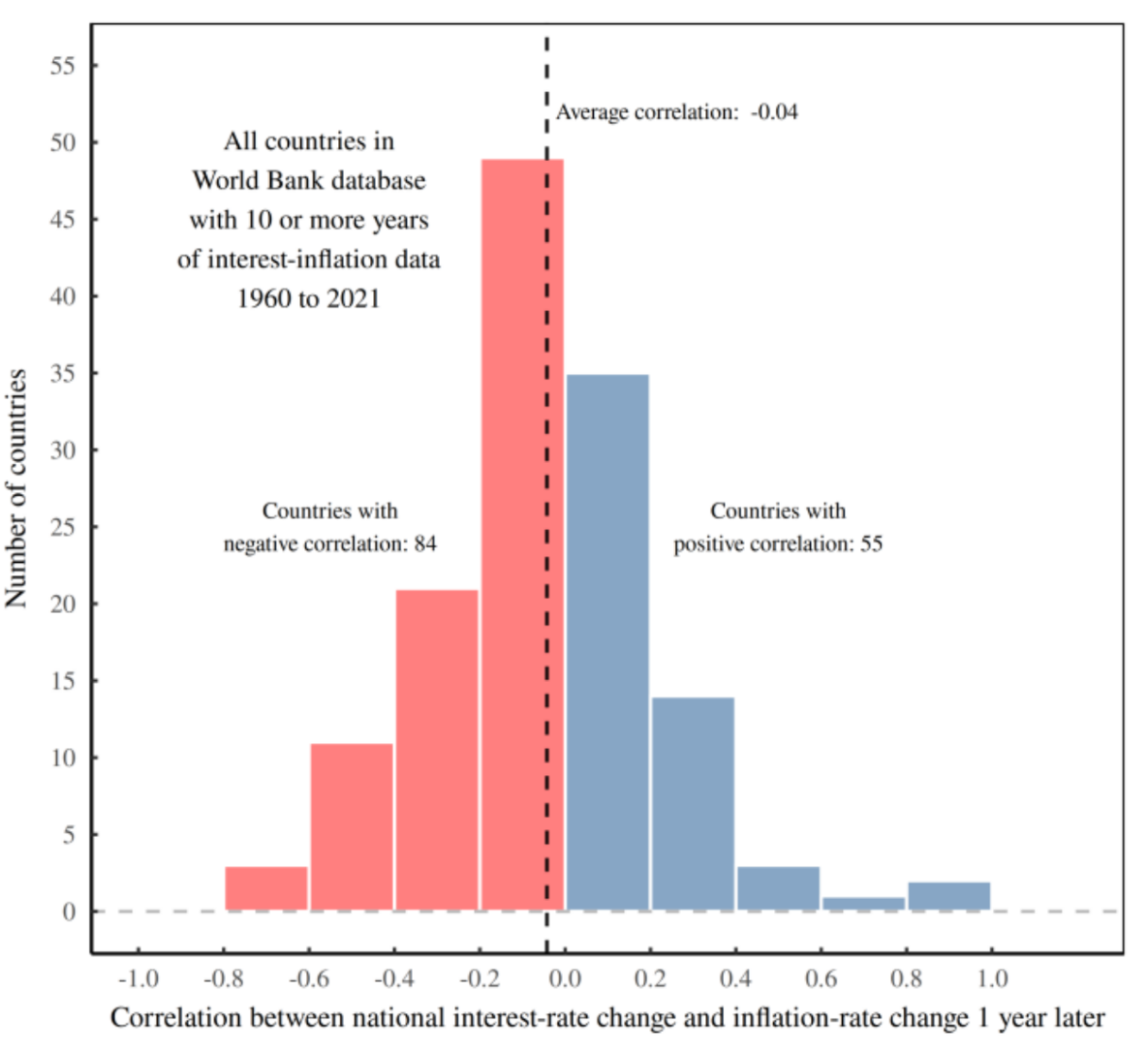

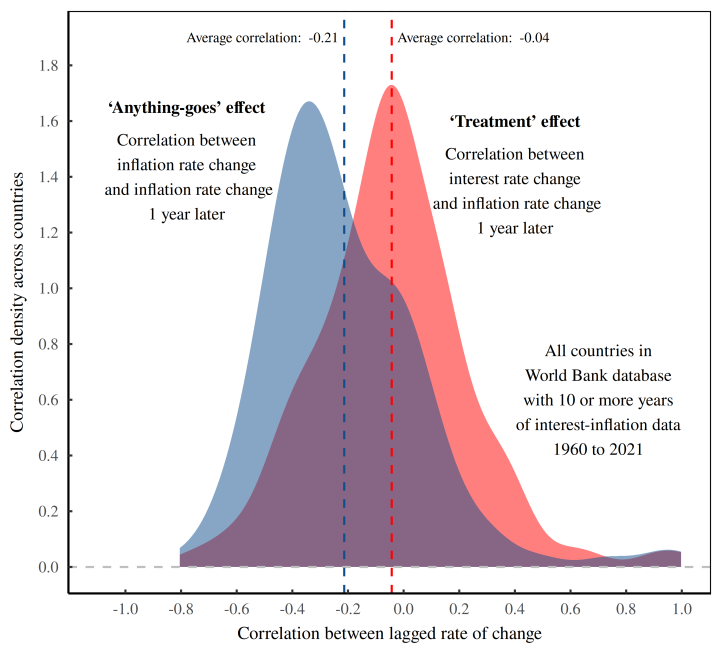

Below is the pattern within countries. The pattern is also quite muddy, with a very small negative correlation of -0.04. It also looks like interest rates work for more countries than it doesn’t.

It’s interesting in itself that if we look at the data between countries or within countries gives us different results. For some, the 2nd graph would be enough, but this tiny correlation isn’t evidence for down-regulation as Blair explains:

“When data is highly cyclical… a lagged effect must pass a huge threshold to be convincing. That’s because anything that co-varies with inflation will automatically predict future inflation. In contrast, when the data is acyclical … any kind of prediction about future behavior is impressive. That’s because the inflation data has virtually no ability to predict its future self. So the hurdle for a lagged effect is small.”

What this means is that if inflation down-regulates itself in a cycle yearly of ups and downs, then interest rates (or anything else) will likely correlate with it. You would find the same thing with wages for example. Hike wages, and inflation goes down the next year because it was going to come down regardless.

Now lets “treat” inflation with interest rates (red) and compare it to inflation lagged on itself (blue). Most of the time the red and blue lines overlap giving us a null result. Though again, large drops in interest rates appear to down-regulate inflation. There’s also a little evidence that rate hikes may make it worse (red above blue).

Now lets look within countries again. Blue is inflation lagged on itself, red is an interest rate treatment. Its rather obvious that inflation has a stronger effect on correcting itself (-0.21) than interest rates (-0.04).

So interest rates covary with inflation, but hikes have little effect on it. The small negative correlation we found before is dwarfed by the effect inflation has on itself. One might even suppose that the small -0.04 we get from rate hikes is due to making inflation worse, a bit like trying to fight fire with fire. -0.04 shows how rarely that strategy works.

As a final remark, I know many of you coming from standard economics must be asking about “real interest rates”. Blair had the following to say:

“By construction, the ‘real’ interest rate is the actual interest rate minus the rate of inflation. If we compare this value back to the rate of inflation, we’re introducing autocorrelation. We’re correlating inflation with the negative version of itself:

Inflation ∼ real interest rate

Inflation ∼ interest rates − inflation

So with ‘real’ interest rates, we have a recipe for defining our theory to be true. In a world in which actual interest rates have no relation to inflation rates, we can use autocorrelation to flip the conclusion. ‘Real’ interest rates appear to regulate inflation. Except that it’s just inflation that is correlating with the negative version of itself.”

This is generally where my summary of Blair’s analysis ends. What follows is mostly my own thoughts and extensions on the matter. If you would like to see a more detailed explanation of the graphs or the methods and sources you can find them in the original posts here, here and here.

Why rate cuts reduce inflation: A case study.

The Turkish Lira was falling against the dollar for some time and in 2022 it started falling even faster. Erdogan responded with cutting interest rates from 18% in March 2022 down to 10.5% in October.

The entire time news outlets everywhere were calling this move crazy. Europe’s Economic Policy Journal released a paper about how “ignoring basic macroeconomics” lead to inflation. Ironically, it was released in October 2022 just before the Lira stabilized.

High interest rates and exchange rate volatility made borrowing in Lira unattractive relative to cheaper and safer euros and dollars. On top of that, opening a foreign currency account was fairly easy. Nearly half of all deposits in Turkey were in foreign currency, not the Lira.

The CB cut rates with the idea of stimulating Lira denominated investment and growth to reduce inflation. Too many dollar denominated liabilities also potentially caused a cycle where drops in the Lira made it harder to pay back those debts.

Perhaps another way to phrase it is that Erdogan’s government did not believe that Turkey was at full employment or the issue was “too much money chasing too few goods” since barely half of deposits were in Lira. There seemed much more room for the Lira and for production.

Turkey underwent a program of “Liraization” with the aim of increasing Lira deposits from 53% up to at least 60%. The plan was to use a variety of regulations and incentives to make accounts in foreign currency less attractive and get people back on the nation’s money.

Spelled out this way, the actions of the Turkish government don’t seem so absurd. Did this actually work or did things calm in spite of the policy? I honestly don’t know. You can watch a more detailed explanation of it here. However, the video also uses a lot of contradictory mainstream economic ideas to justify an unorthodox policy. This isn’t a boon for economics. It’s just cherry-picking and hindsight. As we will see, It is also entirely possible that inflation had just run it’s course. Regardless, congrats to Turkey on the recovery.

Why rate hikes make inflation (a little) worse.

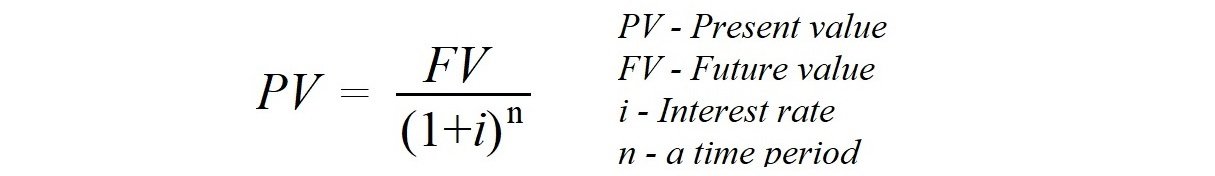

The idea that interest rates could be bad for the economy goes back far enough to be part of various world religions. More recently, Tim DiMuzio suggested that businesses just pass the cost of rate hikes onto customers. This is because most businesses do cost-plus pricing and interest payments get lumped into operational costs. Another way to look at it is that large businesses use discounting formulas to price their goods and services, and this comes with it’s own implicit interest rate.

The value of a loan is the same formula moved around for FV. For businesses to stay afloat, i needs to be equal to or greater than the interest rate banks charge them (and both need to be above the wage rate, as my old professor John Smithin once taught me).

(All values are logged)

Last year (2022), Professors Gormsen and Huber of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business conducted a survey whereby they collected the transcripts of quarterly conference calls from 2002 till 2021. Their team manually extracted data relevant to financial costs from over 74,000 paragraphs (absolute madmen).

What did they find? Well, the following quote appears to validate both Tim DiMuzio and John Smithin above. “Existing surveys suggest that many firms use discount rates greater than the financial cost of capital (Poterba and Summers 1995, Jagannathan et al. 2016, Graham 2022).” Gormsen and Huber also concluded that firms with high market power increase their discount rates in response to larger financial costs, though “significantly less than one-to-one”, whereas firms with low market power decreased their discount rate almost one-to-one with financial costs. It appears as though rate hikes would only work under conditions of perfect competition. Too bad that as we use more energy and develop that is less and less the case.

Professor J.W Mason recently had this to add when reviewing their survey work:

“While this picture offers a striking rejection of the conventional view of interest rates and investment spending, it’s consistent with other research on how managers make investment decisions. These typically find that changes in the interest rate play little or no role in capital spending.”

All of this suggests that the idea that rate hikes might deepen inflation isn’t so crazy, However, If all of these abstractions and referencing goes above your head, I’ll leave you with this excellent anecdote from M. Langdon found in Blair’s comment section:

“Excellent article. I actually worked for Canada’s “Anti-Inflation Board”, as my first real job as a Juniour-G-Man Economist. It was summer of 1976, and inflation was running hot and very nasty in Canada…One thing I discovered, was that — mostly — higher interest rates were typically just passed forward as increased business costs, since most businesses were also up to their eyebrows in debt — and had to either die, or service that debt.

It was bone-bangingly obvious. Raising interest rates caused inflation, because if most economic agents were in debt, the higher rates were just viewed — by both consumers and producers — as higher costs of operation, or higher costs of living.”

What is money worth anyway?

I can say with relative certainty that interest rates don’t regulate inflation because the money supply doesn’t either.

Richard Vague, a firm monetarist, decided to compare theory to data and what he found shook him. He released a study in 2016 that looked at large increases in the money supply for 60 years across 47 countries and found almost no correlation. Money supply increases were slightly more likely to prevent inflation than cause it.

This wracked my brain for years and I was content saying inflation is supply-side. I have another way of explaining the lack of correlation now though. MV = PT is taken as a truism, even by people as critical as Blair. Usually the issues with it are some form of (1) it doesn’t tell the flow of causality (2) velocity is vague and difficult to measure or (3) prices are sticky. It is universally held as correct in the “long run” (remember, the lags are “long and varied”).

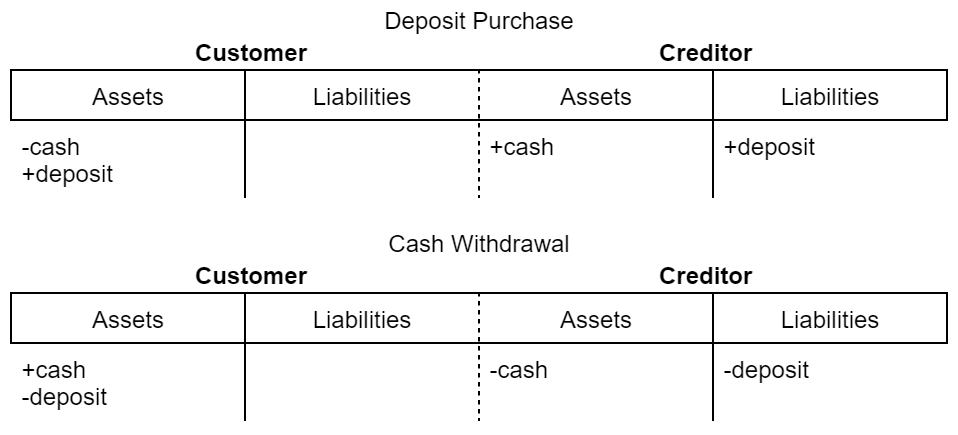

I noticed something was off when I was doing balance sheets for a presentation. One of the instruments was different and didn’t cause inflation regardless of how much was created.

When you deposit cash in a bank or buy a gift card, new money is created at par. In a simple model, this doubles the money supply. However, no prices change.

If we want to add goods and services to the mix, look no further than gift cards.

The reason why is that in spite of money creation going on, there is no change in net-worth for either party. No change in net-worth means no additional purchasing power. While many have mentioned that MV = PT is an accounting identity and doesn’t say anything about causality, no one I have come across mentioned this “accounting identity” doesn’t work with accounting sheets.

Chris Rimmer found much the same thing in 2019. However, this isn’t the only type of transaction or method of money creation. Borja Clavero (2022) details that there are 4 ways to discharge a payment obligation. Some are indeed capable of changing net-worth and purchasing power. I’ll write more about this subject at another time.

Ultimately, if the money supply can’t be trusted to curb inflation then neither can interest rates.

Why would inflation be cyclical and self-correcting?

This is perhaps the most difficult part to write on. Capital as Power was the only 500+ page book I ever had to read 3 times before I could say I really understood it. The book is dense with Nitzan and Bichler attempting to entirely remake economics like no one else. For those reasons, it’s hard to summarize any of their ideas to the uninitiated. To describe it as “Heterodox” is an understatement. Nothing the audience would have learned in economics helps them here.

Central to Capital as Power (CasP) is that businesses compete to beat the average rate of profit, and by doing so create that average. What Nitzan and Bichler found is that inflation (or rather, stagflation) is one of two dominant business strategies for getting ahead. The other strategy is to sell more stuff either by building new factories, acquiring them, or merging with other companies. When the merger waves stop, inflation begins. Merger waves are a bit like bulking up before the big match — Stagflation Showdown: a test of market power.

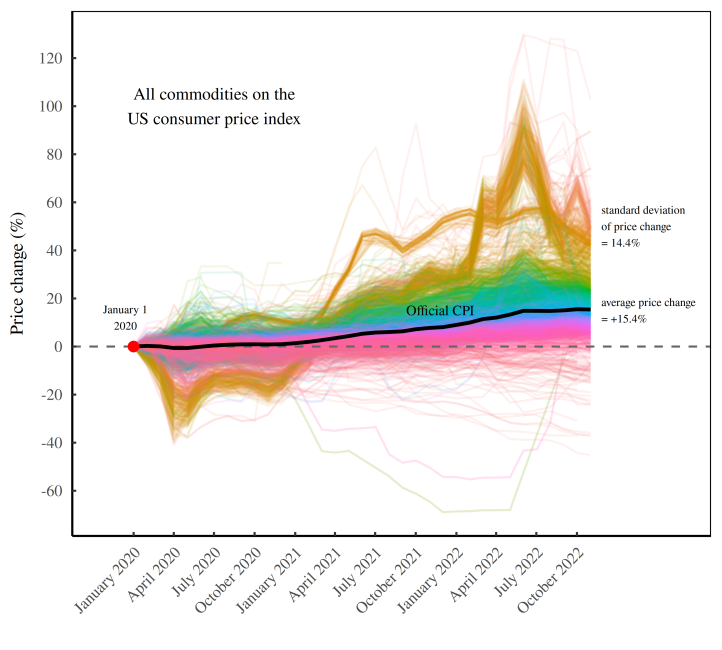

Prices are never level. Some rise much faster than others and some even fall during inflationary periods. Below, Blair shows what it looked like under Covid. The differences between prices far outweigh the average increase. While I see more and more people picking up on this, it’s usually just to pin the blame on a specific sector or whoever and it loses the big picture.

While prices vary considerably, it is perhaps also a mistake to give it a reductionist treatment. Again, the average here is important, but only because businesses don’t want to fall behind the herd[4]. Plenty of businesses use the reported average as an excuse to hike their own prices. Never let a good crisis go to waste after all.

Chopping down the CPI only to whoever is winning ignores the collective herd-like behavior just as much as condensing it to a single number such as a “price level”.

And stressing causality can also also be mistaken, as Blair writes:

“I’m not claiming that inflation lacks a cause. When buffalo stampede, it’s because a few animals got spooked. But the stampede that follows has less to do with the initial stimulus and more to do with the buffalo’s collective reaction. And so it is with inflation. Once the inflation stampede gets going, it has a life of its own. The business herd pushes itself.”

Some bulls are stronger than others and are confident they’ll rise ahead when the running starts. However, this whole strategy is rife with risks and hyperinflation also demonstrates that it has no upper bounds. Companies could find themselves stepped on or trapped in a death spiral.

The ever-mounting risks associated with this strategy make it generally self-correcting. Businesses eventually want the race to end and a return to normal. They can rest up, bulk up, and get ready for the next big show.

Interestingly, Nitzan and Bichler themselves also had this to say about interest rates in 2009:

“Occasionally, policy tightening claims a big victory — for instance, during the early 1980s, when Fed Chairman Paul Volker was congratulated for ‘bringing inflation down’ by sharply hiking the rate of interest. But was tighter policy really the cause of lower inflation? As illustrated in Figure 15.2, by the early 1980s, dominant capital was already busy riding a new merger wave, having no appetite for further inflation.”

Future hurdles.

Personally, I think the 1 year lag may be a little short of a cycle. I’d like to see 5 and 10 year lags. Up one year, down the next may seem normal to use WEIRD folk, but I know for those in the Global South that inflationary periods can be long lasting. Additionally, if its a business strategy for better stock performance then it also makes some sense to compare it to the domestic boom-bust cycle which usually falls somewhere between 5–10 years. The data Blair uses does include countries from the Global South. I would just like to see an extra step taken to look at the differential length of inflation as well.

Spillover effects are also interesting to consider. The need to beat the average in the domestic stock market pushes exporters to inflate other economies. For some import-reliant countries, looking at the stock market from your importers’ countries could act as an early warning sign.

Blair and others have talked a lot about “greed-flation” over the last couple years. Most of this is pointing at record profits during the Covid lockdown. Blair has done a deeper dive and, as I see it, he is formulating a very long proof that price increases can only be pinned on the businesses that set them. I’ve done much the same since seeing Richard Vague’s study on money supply and inflation.

Yet, I still had this to say over the phone with a colleague:

“Okay, yes, you’ve correctly acknowledged that inflation is due to competitive system based on self-interest. Great. Whatever. We’ve already assumed that and we assumed that because we don’t have a way to control self-interest.

So unless you have some sort of policy that is supposed to affect self-interest, then you got nothing. So yes, interest rate manipulation is a placebo, but until then people want a feeling of control over their lives. So we give them the placebo, whatever it is.”

In a way, I worry that we may be undertaking a long-winded proof that businesses are self-interested and compete with one another. Economists don’t just know this, they assume it and take it as a given. This is exactly why they look for other causes of inflation or ways to regulate it. So the real challenge for CasP then is to think of a way to fix inflation by controlling self-interest or finding alternatives.

Joseph Henrich did an amazing study in 2001 that showed people are not inherently self-interested and that is was culturally variable. His aim was to discredit the economic assumption and change the field. Oddly enough, the study is widely cited but virtually unknown to economists. Instead, it revolutionized psychology as their test samples were far too homogenous and they hadn’t taken culture enough into consideration either. While we now know that self-interest is culturally variant, this has done little to inform our economic policy. Our science is built on 300+ years of accepting competition and the literature on building cooperation is far smaller.

The overall mechanism needs more articulating and evidence. There’s a decent idea here about how inflation runs start, though I think more needs to be seen on how they calm themselves or turn into a frenzy. Surveys, such as the one conducted by Gormsen and Huber, may be really useful in showing that the appetite for inflation is over and it’s time for a new strategy. CasP also hasn’t analysed hyperinflation much yet and it would be valuable to know what prevents this self-regulation from triggering. I’m aware that high inflation rates are recurring events in some South American countries and the trifecta of Weimar Germany, Zimbabwe, and Venezuela could also be looked at if only for the sake of precious internet points.

CasP is anti-capitalist and anarchist-inspired. Its ironic then that when I shared with someone the idea that the Fed’s rate hikes are ineffective and inflation regulates itself that at least one person said it vaguely reminded them of Austrian economics (emphasis on vaguely). I am a tad concerned that this can be cherry-picked by folks who have laissez-faire in mind. Remember, marginal utility was a socialist idea about redistributing wealth. The way that Blair writes about mainstream economics makes me think he hasn’t realized how malleable it is and how easily he could (involuntarily) become part of it by tomorrow. #endthefed???

Endnotes.

1. Source: Smithin, J. N. (2009). Money, enterprise and income distribution: Towards a macroeconomic theory of capitalism. Routledge.

2. While Smithin uses real values in his work, nominal values could be used and there would be no change to the diagram.

3. Richard Vague also looked at declining interest rates and found it didn’t correspond with increasing inflation.

4. I’ve tried to write this with as few analogies as possible as Blair himself often spends pages and pages calling economics a “religion” (whatever that word means) and an equal amount making natural science analogies. Both of these ironically distract from the actual science he does. I spend considerable length comparing CasP’s concept of inflation to herding, flocking and swarming. I’m not happy about this, but it was necessary to do for the sake of briefly explaining an approach that very few people heard of. Sadly, this means substituting evidence for explanatory gifs.